Structures in the music sector are struggling, and the very ways in which we make, perform and experience music are shifting. But what have music professionals learned from the crisis so far? What are the things to which we should be paying attention? And what should we do next?

FMQ put these questions to nine persons of influence in Finnish music who have a front-row seat in observing how the crisis is unfolding and what its impacts on the music sector are. The responses from live performers, musicians, creators, orchestras, publishers and music exporters are remarkably similar.

The importance of music emerged as a key point in several responses. The coronavirus crisis has highlighted that music frames various areas of our lives, and also that musicians want to create and perform music and audiences want to hear it, regardless of the circumstances. In times of uncertainty and isolation, music and musicians have brought comfort to many, and more generally the crisis has drawn attention to the broader significance of arts and culture.

Having said that, we must note that the pandemic has also revealed that the structures of the music industry are not crisis-proof and that freelance musicians and non-institutional organisations are particularly vulnerable.

Suddenly this summer

All music events in Finland have been cancelled up to the end of July, and according to Music Finland this will result in a loss of income of up to EUR 127 million for Finnish music, amounting to 19% of the annual turnover of the industry. If this situation is extended to the end of the summer, the loss of income may mount up to more than EUR 150 million, slashing the annual turnover by nearly one fourth.

Freelance musicians are out of work for the spring and the summer, and according to the Finnish Musicians’ Union their loss of income will add up to about EUR 35 million by the end of July. Venues, agencies and individual agents are consequently also hard hit, and bankruptcies may be on the cards.

With symphony orchestras, the outlook is not quite as bleak. When audience events were banned in the spring, orchestras began to plan substitute activities in social media and on online platforms. Some salaried orchestral musicians were laid off as the economy took a nosedive, but many are still working, although in their case work now consists mostly of independent practice and streaming of chamber music performances. Some members of municipal orchestras have transitioned to social services, such as Teppo Ali-Mattila, who plays violin with the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra and now makes food deliveries by moped to senior citizens in quarantine.

As summer approaches, it seems likely that there will be no music festivals in Finland in 2020 [this has changed in June, see our up-dating article here], which will have a major impact on both performers and festival organisations. Things are not quite as disastrous for arts and culture festivals receiving public funding; most of them will probably survive if circumstances have returned to something resembling normal by next summer. However, some major players such as the Savonlinna Opera Festival and Pori Jazz, as well as festivals that rely entirely on box office revenue for their income, may face a solvency problem, particularly if people who bought tickets in advance demand refunds.

Photo: Timo Lassy by Tero Ahonen

Long-term impacts and mental stress

Operators in the music sector are worried not just about the situation at hand but also about the long-term impacts of the coronavirus crisis, because in the close-knit ecosystem of the industry everything affects everything else. From the perspective of composers and publishers, long-term impacts will include a drop in royalties due to live performances being cancelled, music exports tanking, AV productions being suspended and advertising revenue from commercial radio, TV and online services plummeting. Other long-term impacts include commissioning negotiations broken off and losses in revenue from the sale and rental of sheet music. Music publishers estimate that turnover in the sector may decline by as much as one third if the crisis continues far into the autumn.

Exposure for new music is also a concern, because user studies of international streaming services indicate that in these times people tend to listen to older music that they already know. It is also difficult to predict how audiences will behave when concerts are restarted, perhaps in the autumn. Will people dare to show up even if they are allowed to?

In addition to a dramatic decrease in income, freelance musicians and composers are stressed by the constant pressure that they are under in the music industry to reinvent themselves, and this has only increased during the crisis. Under normal circumstances, new pieces and performances are regarded as calling cards that may generate further employment opportunities, but as all this comes to a halt, creative musicians may suddenly feel that there is absolutely nothing that they can do themselves to improve their situation. There is a great deal of psychological inequality here: some are inspired by crisis to create new things, while others get depressed and paralysed.

With the imposition of social distancing and the disappearance of live concerts, we have discovered just how important interaction is in music, as in many other areas of life. Live streaming and concert recordings posted online have been seen as important means of maintaining the connection between performers and audiences in these extraordinary times. But although digital vehicles have risen to the occasion to make up for the loss of concerts, it is hard to see them completely replacing live performances. Human beings are social creatures, and social interaction is an essential part of the experience of going to a concert or indeed a festival. In Finland, the prospect of an entire summer with no music festivals and their social experiences feels particularly brutal.

With the support of City of Helsinki, composer Pasi Lyytikäinen writes daily diary-like miniature pieces that feature everyday phenomena during the social distancing time. On this video Eero Saunamäki performs Snowflakes behind window (14 April). You can follow the project at Facebook, Twitter and Instagram via the hashtag #compositiondiary.

What have we done and what should we do?

With the coronavirus-induced decline of the music sector worldwide, musicians and operators in many countries have joined forces to make appeals on behalf of the sector as a whole. All of our interviewees agree that a new kind of solidarity has emerged in Finland too as a result of the crisis: the music sector has come together briskly to explore solutions in a show of unity and a spirit of cooperation. Much of this cooperation has to do with lobbying, as organisations band together to draft proposals for crisis aid and revitalisation measures submitted to decision-makers.

There are already emergency measures in place to help the music sector, with aid being offered not only by government ministries but also by private foundations and enterprises. Information on national, European and worldwide initiatives has been collected for instance on the websites of the European Songwriter and Composer Alliance (ESCA), South by Southwest and the EU National Institutes for Culture (EUNIC). In Finland, aid mechanisms to which individual freelance musicians and enterprises could apply were whipped up at short notice by the Ministry of Education and Culture, the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment, several private foundations and Music Finland (See also Music Finland's article).

Yet the music sector needs not just emergency aid but also changes to structures that have been found wanting. Long-term structural subsidies with which the music sector could take concrete measures to prepare for the long-term impacts of the coronavirus pandemic, such as the decline in royalties, would also be highly desirable. Organisations also wish that both local authorities and the central government would undertake to support cultural organisations and events during the crisis and to ensure their continued funding thereafter.

Our interviewees pointed out that what is essential in support measures in the current circumstances is to consider the financial ecosystem of the music sector as a whole, including not just individual creators and performers but also the undertakings of all shapes and sizes that exist in the field. If these businesses are not supported, leading to many of them shutting up shop for financial reasons, performers will find themselves in deep trouble even after the crisis is resolved, as many of the bodies that provide and broker employment for them will no longer exist. A huge volume of valuable tacit knowledge would disappear. It is also important to safeguard plurality in the music sector and to ensure continued potential for international activities.

Many of the interviewees also pointed out that it is vital right now to shift the focus of debate from the current crisis to longer-term impacts. Paralysis and inaction would be far worse than any mistakes that might be made in establishing new practices.

Photo: Ultra Festival in Mexico, 2019.

Quaerendo invenietis

We asked our interviewees to share their thoughts on the post-coronavirus future of the music industry. Naturally, this has to do with extensive chains of cause and effect that are impossible to predict with accuracy at this time. As with all crises, there will be winners and losers. Traditional organisations receiving public funding are financially in the best position in Finland, while others face a new unknown. We should note, though, that public funding must not be taken for granted, even in Finland. When governments face financial problems, arts and culture are typically at the top of the list of budget cuts.

It also seems highly unlikely that we will return to things being exactly as they were before all this. But on the other hand: would that even be ideal? Would we want that? Is not every crisis also an opportunity, assuming that it does not destroy absolutely everything?

We have surely not seen everything to be generated by the pandemic in terms of musical content. It is the function of art to invent, and this crisis will surely be no exception. Not only creators and performers but also organisations and enterprises now have the opportunity to think outside the box: they can seize on strategic plans that they have never had the time or the resources to implement. They can also focus on fundamental issues such as whether they want things to be just the same after the crisis as before it. And of whom will the (new) audiences consist?

The coronavirus crisis forces the music industry worldwide to explore new channels and forms of operation. Borders remaining closed represents not only revenue loss but a risk of offerings becoming more limited and nationalist content emerging. This can be turned into a positive if the crisis is not unduly drawn out: local operators now have an unprecedented opportunity for promoting diversity until the borders are opened again. There is room for new material and new names that have so far not been able to break through for one reason or another.

Towards a more sustainable music sector?

We need to be mindful that at this point in time, May 2020, scarcely anything has been decided, and no pathways have been irreversibly shut down. The future, both in music in particular and in society at large, depends on the choices that all of us make as musicians, as audience members and as citizens, and on how well we can work together.

Above all, now is an opportunity for both artists and audiences to rethink their values. Could we rebuild the music sector on an ecologically, economically, socially and culturally sustainable basis? The climate crisis has not gone anywhere despite being eclipsed by the pandemic, and many experts around the world have actually seen the pandemic as a foreshadowing of what lies in store for humanity unless we curb climate change.

On the whole, the year 2020 so far has demonstrated in all corners of the world that people can and do change their behaviour and their habits quickly and radically if need be, even voluntarily (see also this article in The New Yorker). Readiness for change is necessary for enabling sustainable development, not just in music but in other areas of life as well.

We need new practices and sustainable choices in order to find a way to new positive developments in the music sector once the coronavirus crisis is past, so that music professionals will be better able to make a living in the future; so that we will perform, produce and consume music more ecologically than before; so that we would see musical content not as an omnipresent and disposable commodity available free of charge; and so that music could continue to transcend all borders and form a rich and constantly innovative soundtrack to our lives, which themselves will of course also be changed.

Our lives will be changed not only because the coronavirus has forced them to change, but also because we ourselves want our lives to change.

Persons interviewed for this article and the bodies they represent:

- Association of Finnish Symphony Orchestras / Helena Värri

- Finland Festivals / Kai Amberla

- Finnish Music Publishers Association / Jari Muikku

- Finnish Musicians’ Union

- Jazz Finland / Maria Silvennoinen

- Kimmo Hakola, composer, deputy chairman of the Board of Directors of the Finnish Composers’ Copyright Society TEOSTO, chairman of the National Council for Music

- LiveFIN / Samppa Rinne

- Music Finland / Kaisa Rönkkö & Merja Hottinen

Translation: Jaakko Mäntyjärvi

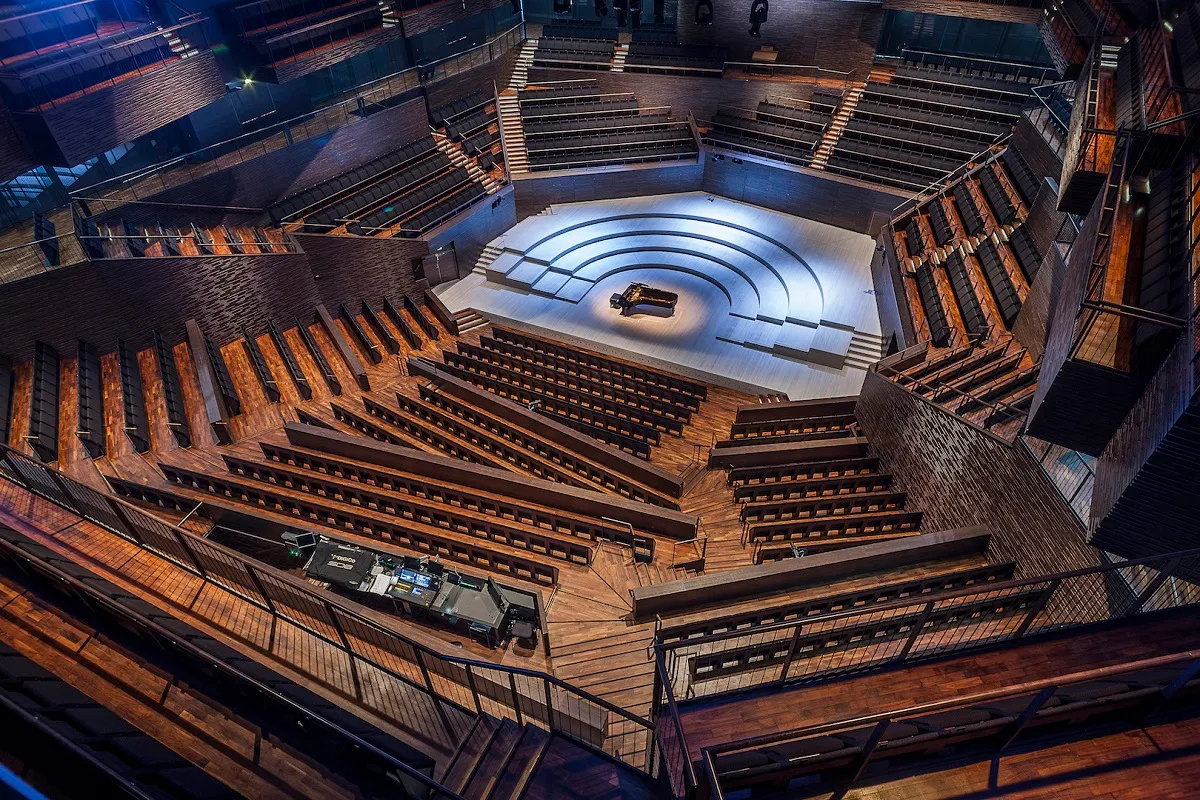

Featured photo by Timo Seppäläinen: The Savonlinna Opera Festival programme scheduled for 2020 will be performed in Olavinlinna in the summer 2021.