Although printed sheet music is still very much the predominant source material in the field of classical music, digital sheet music is increasingly making inroads into the everyday lives of musicians and music institutions. Digitisation brings obvious benefits, including rapid access and ease of use. But there are persistent and quite justifiable doubts about whether completely paper-free music will ever be a thing.

Scepticism aside, the conventional wisdom is that digital sheet music will become hugely more common in the near future. The main issue is how service developers will cater to the needs of musicians.

Improved accessibility for sheet music

Let’s begin with where sheet music comes from. Digitisation has facilitated an unprecedented streamlining in the music publishing business, as sheet music editions can be published both digitally and in hard copy. Jari Eskola, Publishing Director at Fennica Gehrman, still views paper as the overwhelmingly best user interface for music, although he readily admits that digitisation of sheet music is not only inevitable but also essential.

One of the key outcomes of digitisation is accessibility. A major step in this development was taken in autumn 2018 with the launch of a pioneering sheet music streaming service, nkoda. Billed as ‘Spotify for sheet music’, the service is accessible by a monthly subscription fee. Eskola feels that nkoda is the most interesting new thing to hit the music publishing industry for a long time. The service was established by Lorenzo Brewer, a Brit in his twenties who envisioned it from the perspective of digital natives such as himself: a sheet music repository combining ease of use, communality and flexibility.

What makes nkoda special is that it engaged in collaboration with music publishers from the first. As it happens, Fennica Gehrman was the first publisher to actually sign an agreement with nkoda; today, nkoda provides sheet music from a whole range of top-notch publishers, from Bärenreiter to Universal. The more publishers come on board, the more comprehensive the selection will be.

“At present, nkoda has some 30 million pages of sheet music, all accessible legally, covering all genres. And I believe the service will improve further,” says Eskola.

Demand improves usability

Previous similar experiments, such as Gustaf launched by the startup NeoScores, fell apart because of a lack of cooperation. Eskola believes in nkoda, because it was built from the ground up with a sensitivity for the needs of the various parties and with a respect for music.

“It’s the first of its kind, and I believe it’ll become a major player and attract new users at an accelerating rate,” he says.

Meanwhile, publishers have been investing in their own digital library applications, such as the Henle Library or the Bärenreiter Study Score Reader app, which are meant above all for score study. Tido Music is a service created by Edition Peters and a number of other publishers, tailored for practicing. In Schott’s Eulenburg PluScore app, recordings from Deutsche Grammophon are paired with scores.

Musicians tend to be critical of nkoda because it best suits scholars, composers and other people who wish to study sheet music; for actual music-making – rehearsing and performing – it is unreliable and impractical.

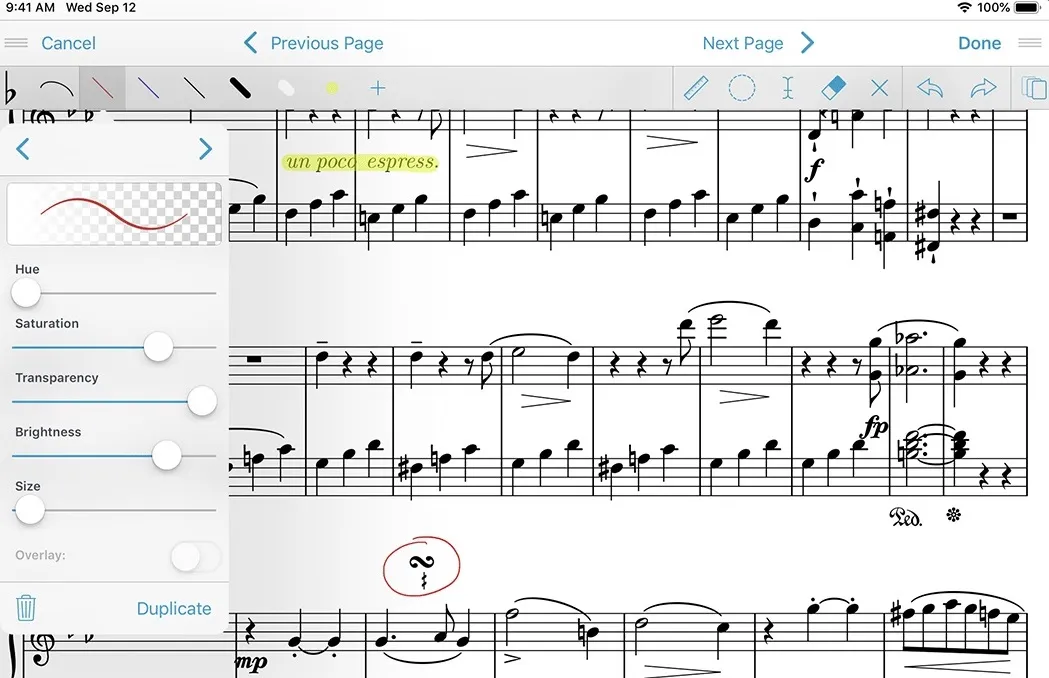

At present, the most widely used sheet music reader on tablets for performances is ForScore. Newzik, intended for orchestral use, was launched a few years ago, and the most recent arrival is Beatik, introduced at the Frankfurt Music Fair in April.

“The problem here is that there have not been tablets large enough on the market, and publishers generally release their digital scores in PDF format, which does not have built-in responsiveness to adapt to different devices. Also, for orchestral playing it would be advantageous to have two pages displayed side by side,” Eskola describes the challenges involved.

In 2015, Apple launched the 12.9-inch iPad Pro, with which using digital sheet music for performance at last began to make sense. Accordingly, the demand for improved digital availability has skyrocketed. Jari Eskola believes that the trend will pick up speed as orchestras acquire more musicians who have grown up in the digital age. Eskola also notes that he has no doubt that the legality of digital sheet music copies can be overseen just as effectively as that of paper copies.

“Publishers have already made provisions for creating digital versions of orchestral parts. When an orchestra comes along asking for these, publishers will be ready,” he says.

Freedom through digital sheet music

The most prominent Finnish ‘digital musician’ today is violinist Pekka Kuusisto, who has been seen operating a foot pedal to turn digital pages on the music stand for years. Musical polymaths Markus Hohti (cello) and Emil Holmström (piano) also often use an iPad to display sheet music. For soloists who use the sheet music mainly as a memory aid in performance, a tablet is a good solution – as long as the tablet and page-turner pedal can be trusted. Musician and conductor Taavi Oramo is also a convert. For the moment, ForScore is the most commonly used sheet music reader in Finland.

Holmström first tried out digital sheet music five years ago, and since autumn 2018 he has been using it increasingly.

“I obtained a better iPad and a digital pen at that time. A tablet is the most useful in situations where page turning and/or lighting is a problem. In projects where a lot of the music is distributed in PDF format anyway, there is a fairly high threshold to begin printing out the scores and taping the pages together just for one performance,” says Holmström.

Taavi Oramo adopted digital sheet music in 2016 and never looked back. He conducts all of his concerts using a tablet. Turning pages with a pedal is for him the single greatest advantage in the setup.

“Your pedal technique improves and gradually integrates into your body language. Also, you always have all your scores with you, and ForScore always keeps them in order, unlike my bookcase back home,” says Oramo. A conductor reading a tablet to conduct an orchestra is still a rarity; almost every time someone in the orchestra remarks on the fact to Oramo. (See also Oramo's interview in FMQ.)

"Digital sheet music will come to orchestras at some point, certainly. The question is when and how." Sebastian Djupsjöbacka / The FRSO

Soprano Tuuli Lindeberg first sang from a tablet as a soloist in Bruckner’s Requiem last Easter. She has been using digital sheet music increasingly since last autumn, particularly when practicing. Although printed sheet music is still the primary source for her, she sees the many advantages of its digital counterpart.

“There’s no sense in having a copy of every single piece of music on the shelf at home, considering what a huge amount of repertoire I go through every year,” says Lindeberg, who specialises in Baroque and contemporary music. “There are many great public-domain editions available in the subscription-based International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP) (also known as the Petrucci Music Library), and I can easily practice contemporary pieces with the sheet music on a tablet.”

Composers of new works tend to send new pages with corrections as the premiere approaches, and all this is easy to keep in order using a pad; also, when memorising a new opera, for instance, Lindeberg can work anywhere at all. For her, the major drawback in using a tablet is that it is cumbersome to make annotations.

“There are a lot of special markings that singers use. It is a bother to enter things like ornaments and text notes in ForScore when you have to do it on the fly, such as in an orchestra rehearsal.” Lindeberg also sometimes misses the weight and feel of a paper copy and the overview of the progress of an extensive work that comes from turning the pages of a printed score. Yet she is also determined to continue learning how to use ForScore and plans to use a tablet for many of her performances this summer. (See also Tuuli Lindeberg’s interview in FMQ.)

Photo: Heikki Tuuli

Building confidence?

Emil Holmström also uses ForScore. He uses a smart pen for making annotations and finds it convenient.

“Initially, I was extremely irritated by how clumsy it was to enter annotations, and I didn’t use a tablet for practice, only for performances. But with a well-functioning digital pen, it is quicker to make annotations than by hand, and it doesn’t distract from the learning process.”

That said, Holmström prefers to practice using printed sheet music, because a tablet screen is not pleasant to stare at for hours for end, not to speak of having to keep an eye out for battery life. In most cases, he shifts to digital sheet music for the final stretch, and he performs with a tablet and turns pages using a pedal.

“Printed and digital sheet music exist side by side in my world, and I hope that this arrangement could be perpetuated and improved,” he sums up.

Reliability is paramount when talking about digital sheet music. Taavi Oramo notes that a single glitch can destroy one’s confidence in the system if it happens during a concert. He has tested several pedals and selected the one he feels suits him best. He is comfortable with using technology and is adept for instance at changing the page size in sheet music files.

“There are still lots of little things that you have to remember to take care of yourself. Because of this, digital sheet music is not yet a completely transparent and universally applicable thing,” Oramo says. He considers that tablets should become cheaper and more reliable for digital sheet music to become more widespread.

“I do believe that we will give up hard copy at some point. Digital sheet music just has so many advantages. But do we have hardware good enough to enable it?”

Infrastructure needed for orchestras to make digital leap

The Newzik application is based on the premise that orchestras must be allowed to make better use of technology. The company has run several pilot projects with orchestras in developing a sheet music reader tailored for orchestra musicians. The musician surveys reported by Newzik on their website indicate that the majority of the musicians participating in the pilots have been pleased particularly with the page-turning function and the possibility of sharing electronic annotations with other users. The application also has other useful functions such as the option of viewing the parts of other musicians at a selected point in the score.

Newzik is widely used at the Vienna State Opera and by the Orchestre National d’Île-de-France, the latter having performed its first all-tablet concert in October 2018. This was not the first of its kind ever, though; the first concert performed using iPad Pro tablets only was held jointly by Newzik and the Rouen Opera Orchestra in autumn 2016.

Newzik assures users that it has addressed the concerns related to tablet use: scores with user annotations are stored in the cloud, and performances can be made safely in offline mode. They have even given thought to digital eye strain, or screen fatigue.

For all these bright examples, however, the notion of an orchestra going fully digital still seems like a pipe dream, at least if one asks someone in the thick of an orchestra’s sheet music management: a music librarian. Sebastian Djupsjöbacka, music librarian of the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, reports that the music librarian profession has been actively pursuing the adoption of the newest technology for some seven years now. For instance, they were involved in beta-testing nkoda, which Djupsjöbacka considers a highly promising service.

Digital sheet music is already being used by the FRSO in many ways: in planning, material preparation and home practice. For the music librarian, the major threshold for the idea of performing concerts using digital sheet music is how to ensure accessibility of the material. He considers that even the iPad Pro is too small for orchestra use, particularly for certain instrument groups such as percussion. Generally, he feels that digital sheet music is not quite yet a suitable replacement for hard copy, as printed sheet music is still by far more comfortable to look at and more convenient to use. The bright screen of the iPad may even constitute a health hazard. Besides, having a hundred tablets for a hundred musicians would require a complex infrastructure for keeping every device charged up and in working order, not to speak of the issue of device security and functioning.

“But digital sheet music will come to orchestras at some point, certainly. The question is when and how. Music librarians want to be actively contributing to this.”

Featured photo by ForScore

Translation: Jaakko Mäntyjärvi

More about the software presented in this article:

nkoda - sheet music streaming service and sheet music reader with some 30 million pages of sheet music, all accessible legally and covering all genres

forScore – the most widely used sheet music reader on tablets for performances at the moment

Newzik - a sheet music reader tailored for orchestra musicians

Discussion continues on digital scores

BY Anu Ahola

The outlook for digital sheet music was discussed at a conference at the Classical:Next event in Rotterdam in May 2019. Aurélia Azoulay, co-founder and head of business development of Newzik, moderated a session that explored the challenges and opportunities of digital scores considering the needs of orchestras and other institutions. While the starting point for the session was the Newzik music reader application, the discussion covered a wide range of more general issues, visions and doubts related to the digitisation of sheet music.

It emerged that for many orchestras the (un)reliability of the technology in performance still remains a major sticking point. Another obstacle to the wholescale adoption of digitisation for institutions is the huge cost involved in procuring tablets for an entire orchestra. And how would a digitised orchestra work with guest freelancers who may not have a tablet to work with?

The feedback from the orchestras - as well as from the musicians who had actually tested the Newzik system - was largely positive. It was particularly interesting to learn that attitudes to digital sheet music did not correlate with age; older musicians were quite as keen to adopt the system as young ones.

This is not to say that printed sheet music is going out the window. It was noted in the discussion that hard copy will continue to be used alongside digital sheet music, for instance because of availability and (better) reliability, but also for sentimental reasons. Many musicians still feel that there is a distinct and unique feeling in playing from a printed page. On the other hand, there seemed to be broad agreement that using two formats side by side – paper and digital – would hardly be feasible in the long term.

When the discussion turned to the role of publishers in the process of digitising sheet music, a representative of a major publisher noted that publishers absolutely want to be involved in the development of digitisation but that transferring centuries of repertoire to digital form requires a huge amount of time and money.

The session included some interesting visions concerning the future of digitisation. A digital score is already being seen as a ‘master score’ to which the entire orchestra can contribute. And probably in the longer term, digital scores will no longer be printed scores scanned into PDFs but an entirely new format for music notation – a format that is work in process but whose appearance and entire potential we can probably not yet even imagine.