It was around this time that Magnus Lindberg wrote: “Finnish musical life has a tendency to speak of coherence and a command of large-scale forms when what it really means is boring and repetitive, and vice versa, to speak of chaos and an inability to formulate music when what it really means is richer variation and innovation.”

The birth of the Avanti! Chamber Orchestra was proclaimed by the young conductors Esa-Pekka Salonen and Jukka-Pekka Saraste: “We begin with the composition, not the institution. We choose an orchestral line-up to fit the music, not music to fit the orchestra. This is the heart of what we do, and the basic Avanti! principle. Avanti! does not specialise in any particular genre or era – and precisely this is unusual these days. We also feel responsible for promoting the music of our own day and age. Our field is boundless. Avanti!”

Avanti! was not founded as a new-music orchestra. Nor was it by definition a generation orchestra, for among its founders were some older musicians and persons of influence in Finnish music. Among them was Ilkka Oramo, the Sibelius Academy Professor who hit on the idea of the Summer Sounds festival first held in the little coastal town of Porvoo in 1986.

Avanti! is built on democratic lines. Letting every voice be heard has sometimes been time-consuming, but as a body, the orchestra is also capable of stretching itself and making sacrifices in order to achieve its ends. It was also rare for a Finnish orchestra to have close ties with the business world.

“An alliance such as this between money and the arts does, of course, raise a host of questions and speculations,” wrote the press in the early 1980s. The orchestra, too, had its doubts about ‘filthy lucre’: would it call the tune? But without its sponsors, Avanti! would never have got off the ground, and collaborating with the private sector has not clipped its wings.

Darling of the media

In next to no time, Avanti! became the darling of the media, showered with praise in the press and raising only a few eyebrows.

“It is some time since anything as significant as the founding of an orchestra like Avanti!, aware of its duty to perform the very latest music as well [as the classics], has occurred in Finnish musical life,” wrote Olli Koskelin in the journal Synkooppi in 1984.

“Wherever Avanti! goes, something unexpected, delightful, essential to our musical culture and all in all vital takes place.” (Veijo Murtomäki in the leading Finnish daily Helsingin Sanomat, 29.6.1986.)

“No suggestion of being burnt to a frazzle, stuck in a rut or frightened of life. They have the courage to criticise existing conditions, to seek new outlets; for that which lives, strives onwards. The very existence of this ensemble is a manifestation of the zest for life of music in Finland.” (Outi Pennanen in Kotiliesi vol. 21, 1987.)

“This is the best band Finland can produce.” (Esa-Pekka Salonen in Ilta-Sanomat, 26.6.1986.)

Veijo Murtomäki, again writing in Helsingin Sanomat, proclaimed that “Avanti! is like King Midas. Whatever it touches turns into gold.” But in 1989, Olavi Kauko reckoned in the same newspaper that Avanti! was going downhill. The honeymoon with the media was over.

The day-to-day running of the orchestra called for a lot of juggling. In the early years, a large number of the players were students, but many of them soon got regular posts in other orchestras. This did not reduce their keenness to continue in the ranks of Avanti!, but it did make scheduling difficult.

Premieres and critical programming

‘Critical’ and ‘century-spanning’ are like two leitmotifs in Avanti!’s programming. For the orchestra’s first concert in 1984 it chose Richard Strauss’s Le bourgeois gentilhomme, Maurice Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin and François Couperin’s L’Apothéose de Corelli. Curiously, all three were new to Finland.

Before long, Avanti! had shouldered the chief responsibility for premiering music by the young generation of composers. New works by Magnus Lindberg, Kaija Saariaho, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Jouni Kaipainen, Kimmo Hakola and many others were given totally committed and highly charged first performances. Inroads were also made into modern music, one work at a time – the Stravinskys, Schoenbergs, Berios and Ligetis.

The classics were also high on Avanti!’s list of priorities. It wanted to show that the history of music is not a museum for antiques but an incubator for new ideas. To bear this out, Salonen and Saraste in turn conducted the Beethoven symphonies at the first nine Summer Sounds festivals.

Flautist-composer Olli Pohjola, Avanti!’s ‘firebrand’, described its objective in provocative terms in 1987: “Our aim is to arouse A) Unrest and conflicting thoughts that force people to reassess what they value in life; B) Anxiety and fear, but also a sense of responsibility for the future of our world; C) Indignation and even FURY that can be channelled into action at the rot in society; and D) Disapproval in law-abiding citizens with a respect for good manners.”

From tailspin to tranquillity

The pace of work at the Summer Sounds festival became nothing short of infernal, until the ‘catastrophic’ festival of 1989 that had the players frantically trying to be in two places at once. Rehearsals were held by night, music got lost by day, and people began to crack.

The end of Avanti!’s flight into orbit coincided with a crisis in the national economy and Finland’s banks. In late 1988 and early 1989 Avanti! ran a ‘tailspin’ festival offering, according to the programme notes, “B music in B performances to B folk”.

The financial and administrative losses incurred by Summer Sounds led, in the early 1990s, to reorganisation. Olli Pohjola stepped down as Artistic Director, to be replaced by Avanti! leader and conductor Sakari Oramo in 1998. “Initially,” said Oramo, “Avanti! changed society; later, it was dragged along by the changes in society. The forces rending the nation in two in the economy triggered a defence reaction in Avanti! too – rationalisation, an international orientation, and reorganisation.”

This did not tame Avanti!, but in the 1990s it aimed above all at honing its projects and smoother decision-making. It was plain to see after 15 years that many new trends in music had been channelled to Finland via Avanti!. The orchestra had trained legions of musicians and composers, and the annual growth rings for the late 20th century encompassed a wealth of music in the Avanti! image, all inspired, virtuosic and groundbreaking.

Life out of a suitcase

Avanti! has become Finland’s most international and most ‘intermusical’ orchestra. From its very first steps, it has set a course towards different genres of music, different audiences and countries. In the international domain, it soon became Finland’s musical flagship, sailing all over the world as an ambassador for the arts in Finland. One of its most memorable journeys was a safari tour of Tanzania in 1992, when it performed the Accordion Concerto by Erkki Jokinen in mud huts.

Popular music has always also been an item on the Avanti! agenda. Leading the way here has been Humppavanti, an ensemble with a relationship to tradition as complex as that of the mother ensemble. The Finnish popular tradition has proved to be a high-selling export commodity. In particular, the once morose Finnish tango seems to go down a treat. Also legendary are the Avanti! children’s concerts that have introduced a lot of music for young listeners into the concert repertoire.

An anti-institutional institution

Avanti!’s opening gambit was “We begin with the composition, not the institution”. Back in 1987, violinist John Storgårds was already describing his band as “an institution, but a free one”.

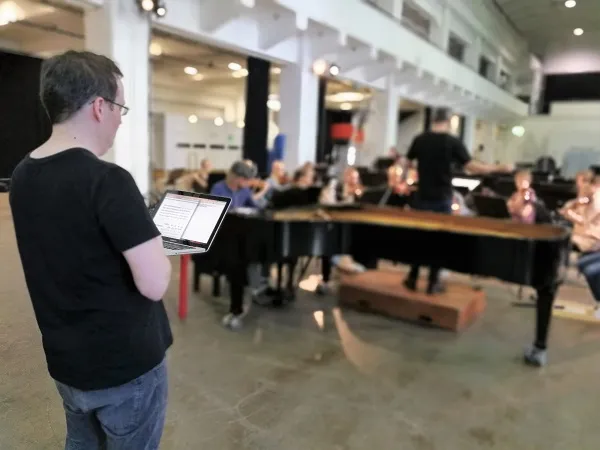

In 1992 the orchestra acquired a fixed abode at the Cable Factory and the following year it was granted enough state aid to pay the salaries of its office staff under the new Act on Orchestras. The players’ wages have still not achieved institutional status.

Even by international standards, Avanti! is a rare bird. This applies both to its repertoire and to its idealistic set-up. As an orchestra dedicated to contemporary music it could be likened to, say, the London Sinfonietta, the Ensemble Intercontemporain or the Ensemble Modern, but it does not confine itself exclusively to new music, and its players are not civil servants.

As cellist Anssi Karttunen, who took over as Artistic Director in 1994, put it: “Avanti!, which was born as an anti-institution, has transformed from a phenomenon into an institution. What, then, is its biggest challenge for the future? Because our principles are already visible in the work of many other musical institutions.”

“But even if one generation has learnt something, the next one will not automatically be just as broadminded. Our world is fast assimilating a tendency to standardise, specialise and dumb down, and its prejudices are more and more deep-seated.”

No borders in sight

In 1999, on taking over as Artistic Director, clarinettist Kari Kriikku was likewise pressed into expressing his views on the institutionalisation of his orchestra.

“Avanti! is already an institution. This could mean that its operations have become stolidly official, that the grants roll in and the phones are answered. But the fact that the players and their music are where and when they are meant to be is not a sign of senility. And the desire to experiment is still as strong as ever.”

Proof of this are the themes and programmes of concerts since the beginning of this century. Avanti! continues to make statements that surprise and irritate, that kick at expectations, ossification and intransigence – in other words, institutionalisation.

Under Kriikku, Avanti! concerts have covered Soviet avant-garde, design, love, racism, politics and mechanical music. Each year, a guest composer is invited along to lend the Summer Sounds festival a personal touch: Hans Werner Henze, Franco Donatoni, Helmut Lachenmann, Per Nørgård, Oliver Knussen, Anders Hillborg, Colin Matthews, Mauricio Kagel or Jonathan Harvey, for example.

Despite its versatile, popular, highly acclaimed and award-winning work, Avanti! does not feel there is nothing left for it to do. On the contrary, the world is increasingly lacking in vision, and the role of music in it is becoming more and more insignificant. The trend is to concentrate and categorise the arts, to command them to stay where they are told. Avanti!’s field is as boundless as ever.

Historian Antti Häyrynen is a freelance journalist and a writer on music. He has written programme notes for Avanti! over 20 years.

Translation: Susan Sinisalo

Featured photo by Heikki Tuuli: Avanti! goes popular: Humppavanti at the Tavastia Club in 2010.