Contemporary-early music – towards a merging of styles

An East–West dialogue and interpolation of melodies from Christian, Jewish, and Arabic musical traditions have been a subgenre of sorts on the early music scene for some twenty years now. Projects of this kind highlight the blending of influences and geographically extended roots behind music that we consider ‘European’.

Within historically informed music-making in Scandinavia, an equivalent has emerged in the form of ‘folk baroque’. It draws inspiration from similarities between early performance practices and local folk music traditions. Kreeta-Maria Kentala, for instance, a leading baroque violinist and one of the early music pioneers in Finland, has tapped into her Ostrobothnian fiddling background in projects juxtaposing folk tunes from Southern Ostrobothnia and baroque music, resulting in the albums Side by Side (2016) and Polska Pandolfi (2021).

The musicians of the past probably resembled folk and jazz musicians of today rather than specialised contemporary classical instrumentalists, and the rich folk music heritage of the Southern Ostrobothnia region, centred in the town of Kaustinen with its folk music festival, resembles the passing of oral know-how in baroque times and earlier. Musicians handling the earliest repertoires seem to be increasingly tuning into this affinity. New paths are being made, and traditions are melting into one another.

Ilkka Heinonen, originally a double bass player in the folk and jazz music scene, found his way into early music via the jouhikko, a Finnish bowed lyre, and is now creating uniquely sounding music with this primordial Karelian string instrument. His album Käki, released in 2023, documents his more than twenty-year journey with the instrument, serving as both a thoroughly researched exploration of Karelian jouhikko playing and a liberating manifesto of its undiscovered potential. The jouhikko’s origins as a dance-accompanying instrument and its role in Karelian culture blend with influences from medieval Finland, religious songs of the Eastern Church, and echoes of the European Renaissance. Heinonen pays tribute to the Karelian jouhikko players of the nineteenth century, whose music-making can be glimpsed in transcriptions from the early 1900s but brings their legacy to life as entirely contemporary – or rather, timeless – music.

In Heinonen’s hands, the simple but powerfully expressive, fragile yet versatile jouhikko seems to embody nearly all bowed instruments in the history of Europe and beyond. His love for the viola da gamba, in particular, resonates in the original compositions – or rather, fixed improvisations. A range of six completely different sounding jouhikkos, encompassing reconstructions of both Estonian and Karelian styles, and a variety of bowing techniques create an exciting web of styles and tone colours, from soft and dark to earthy and whimsical. Tensions between sacred and profane, and East and West, add to the mix.

Heinonen makes the jouhikko evade all definitions and embraces its limitations – the small range and its inherent roughness – as creative strength. Jouhikko can emulate the heavenly singing of viola da gamba or sound richly as the tolling of Orthodox church bells, but Heinonen doesn’t try to smooth out its gritty identity, nor does he let it constrain himself. However, far from being carnivalesque or a stylistic potpourri, the album sounds meditative and coherent. Executed without electronics or track layering it concentrates on Heinonen’s solitary process, nurtured for over a year. Acoustics resembling a Finnish medieval stone church was added in postproduction.

The titular track, “Käki” (‘The Cuckoo’), brims with associations. The distinct cuckoo call evokes Finnish birch woods with their nostalgic undertones, but it also recalls early Baroque instrumental music, where the cuckoo was one of the most frequently imitated nature sounds. The cuckoo, a bird that lays its eggs in the nests of others and leaves its young to hatch in unfamiliar families, provides an apt metaphor for the stylistically unrestricted musician. Like the cuckoo, they allow musical genealogies to blend, but they also take other musical creatures under their wing.

The musical journey of Ilkka Heinonen can be fully appreciated on the latest album by the Ilkka Heinonen Trio, which he has formed since 2012 with percussionist Mikko Hassinen and double bassist Nathan Riki Thomson. Lohtu(‘Comfort’, 2021) marks the ensemble’s return to recording after a lengthy hiatus and blends shades of experimental rock, folk pop, Baroque, and Klezmer, to name a few, all infused with an electronically enhanced folk sensibility and Nordic mysticism. Images of polar tundra and Near Eastern deserts flicker side by side. Heinonen’s jouhikko can sound like an electric guitar, a violin, the Armenian reed instrument duduk, or traditionally Karelian and fragile. At times, he buries the jouhikko deep in electronics or sings to his own accompaniment, evoking the ancient spirit of rune singers and lamenters. The listener is compelled to abandon all expectations and, as with the track “Vimma” (‘Fury’), let the music flow from a singular yet multi-faceted source.

‘Gamut’ refers to a series of six pitches or a six-note scale used in medieval solfège, with the pitches named ut, re, mi, fa, sol, and la. Thus, the first two albums by Ensemble Gamut!, UT and RE, lead one to anticipate the complete gamut – a series of six future albums exploring the creative potential of the ensemble’s namesake.

If UT provided a buoyant introduction to Ensemble Gamut!’s unique approach to music-making, RE presents something wildly different. It would be surprising if the forthcoming albums did not each represent a new step in the ensemble’s artistic gamut, which primarily consists of Aino Peltomaa on voice and harp, Juho Myllylä on recorders and electronics, and Ilkka Heinonen, who plays violone and tenor viola da gamba alongside his jouhikkos. The adventurous harpsichordist Marianna Henriksson also features on UT.

Even though early music serves as the link for the ensemble’s core lineup, their albums by no means restrict themselves to this category. Ensemble Gamut!’s idiosyncratic sound deftly navigates a path between styles, traditions, and classifications, often stretching that in-between into an exhilaratingly wide landscape of musical originality. The same applies to their choice of instruments, playing techniques and stylistic practices. The sleeve notes naturally blend a colloquial ease with rigorous manuscript and provenance details.

In contrast to the typical early music approach, historical music is not unearthed, reconstructed, or resurrected; rather, it is brought to life in the here and now, as the musicians seem to step into the skins of their imaginary counterparts from the past. Everything is grounded in thorough scholarship, but when it comes to the outcome, intuition, enjoyment, and imagination take precedence, leaving ample room for the listener’s own interpretations and emotions.

In this process, distances in time and geographical space tend to vanish. On UT, the melodies and texts of Finnish folk tunes and late medieval or early Renaissance songs from Southern Europe create a shared landscape of bittersweet longing and hypnotic dance moves. Mesmerizingly, tunes from the shores of the Mediterranean and the Baltic Sea begin to merge into one another, as heard in the opening track “Ondas do mare/Rannalla itkijä”.

On RE, Ensemble Gamut! journeys into the depths of medieval Finland and its various uses of music, encompassing both Christian and Pagan traditions, solitary and communal experiences, as well as the spiritual and the everyday. Clearly, all these categories blend into one another. Bishop Henry (Henricus), whose story is introduced by Finnish rap artist Paleface (Karri Miettinen), serves as both a domestic saint and a tool of violent oppression, while the Virgin Mary is invoked to heal wounds through mystical whispers.

Indeed, blood emerges as the ambivalent key image of the album, representing violent territorial conflicts – ever present in our world – as well as martyrdom and childbirth, symbolising the cycle of death and life. Improvisation embodies this cycle, forging links between monastic chants and traditional Karelian rune singing, bridging our times and the past. In comparison to the debut album, the atmosphere is more contemplative, even sombre, creating a mystical spaciousness within the compositions.

Especially among Finnish freelance musicians today, being a stylistic omnivore is anything but an exception. A true fusion, however, is something quite different and rare. Ensemble Gamut! excels in this regard by shedding the burden of classical tradition, most notably the reliance on sheet music. A visceral connection to the oral tradition makes a tremendous difference. Each track is a creation in its own right, as different ingredients are mixed together, stirred through improvisation, and enveloped in a warm studio sound.

Most notably on UT, which showcases the stylistic range and interests of the ensemble, elements of early and world music, pop, and jazz dance together in the spirit of street fiddlers and garage jams. The album is characterised by a sense of playfulness and effortlessness that invites the listener to share in the joy. Liberated from notated arrangements, the instruments organically switch roles. Heinonen plucks and strikes his instruments, creating a vast variety of textures ranging from soft singing to churning chords. Myllylä’s flutes mimic the human voice, percussion, or, in the case of the immensely low Paetzold recorder, an electric bass.

Juho Myllylä treats recorders of various sizes and models as if they were extensions of himself, using them to move freely across styles. His projects incorporate elements of jazz, electronic, and film music, among others. He is also a guitarist, singer, and songwriter for the alternative rock band Burntfield, established in 2012. From 2014 to 2021, Myllylä was active in a trio called Ugly Pug, where they played contemporary music on early instruments. Their 2021 album Crossroads features compositions they have commissioned over the years, showcasing three Finnish composers as well.

Labeling Aino Peltomaa as the leader of Ensemble Gamut! would indeed be misleading. Rather, she adopts the role of a singer-songwriter as the key figure within the ensemble. Her voice captures the essence of oral music traditions, possessing a sound as natural as breathing – a song meant for oneself and loved ones, not for an audience. Since the beginning of her career, she has explored her voice, trained in medieval music, in various contexts. Her 2016 debut album, Harmony of the Spheres, combines Antti Peltomaa’s electronic soundscapes, Jorma Kalevi Louhivuori’s trumpet improvisation, and her meditative singing, creating cosmic sounds around the songs and texts of Hildegard of Bingen (c. 1098–1179). Hildegard has since been a significant influence for Aino Peltomaa, and the medieval powerhouse – abbess, philosopher, composer, mystic, and healer – features prominently in most of her projects.

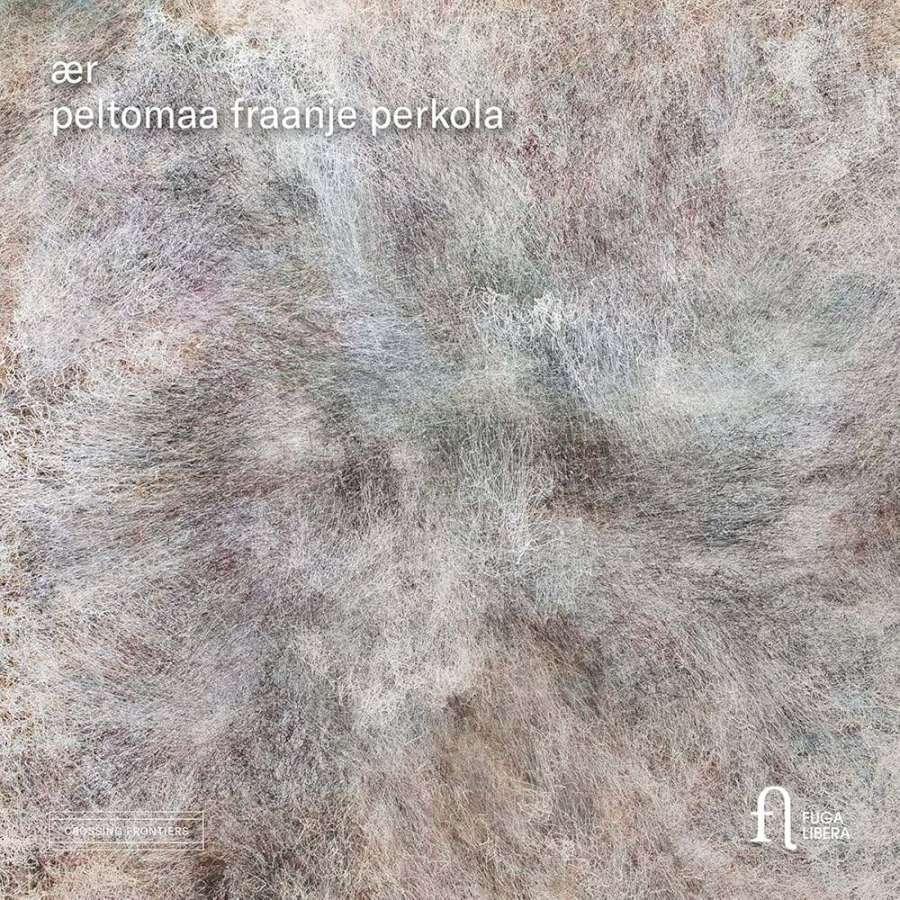

Alongside Ensemble Gamut!, Peltomaa is also active in the trio Peltomaa Fraanje Perkola, which have released two albums to date on the esteemed classical label Fuga Libera. Together with Dutch pianist Harmen Fraanje and the idiosyncratic Finnish viola da gamba player Mikko Perkola, Peltomaa creates extraordinarily beautiful soundscapes that blend medieval melodies with elements of electronic music, minimalism and jazz.

Their debut album, titled Ær (2021), is a meditative journey through time and space. Echoes from vaulted cathedrals and pilgrimage routes create a translucent vapor of sound – a mystical, luminous haze. The title refers to air, breathing, lightness, and spirit. Hildegard’s songs and 13th-century chants by Pérotin form the foundational material, reinterpreted and distanced through improvisation, connecting the ancient, the present, and the distant future. One of the most beautiful tracks, “Rain”, is also one of the album’s original compositions, where the image of the biogeochemical water cycle parallels the organic cycle of musical influences. Humanity and the human ego seem to dissolve into natural elements in a floating softness and elongated slowness, as the trio’s instruments are electronically layered and fused together.

Fragility, a recurrent theme for the trio that also relates to ecological crises, is deeply explored in their sound – and in the compelling artwork by Reinoud van Vught featured on the cover. Aino Peltomaa seeks the limits of quietness and smallness with her voice, stripping it down to a minimum, barely more than a shimmering string of air. At times, this approach feels overly strained, especially in comparison to the wonderfully relaxed vocals found on Ensemble Gamut!’s albums.

Peltomaa Fraanje Perkola’s second album, Komorebi (2023), continues to elaborate on the fragility of our endangered planet and our connectedness with it. The harmonious coexistence emphasized in far-eastern thought is encapsulated in the Japanese word ‘komorebi’, meaning ‘sunlight shining through tree leaves’. Medieval chant still resonates in the background, now in the form of Brigittine songs preserved in Naantali, Finland, but the tracks are mostly original compositions by the trio or its individual members. Additionally, there are lyrics by Peltomaa and the Finnish poet Saima Harmaja (1913–1937).

Compared to the graceful balance of recycling and recreating on Ær, Komorebi resembles more a series of session recordings. While laying bare the method of meditative improvisation and inviting the listener into this musical togetherness is a beautiful idea, it does not occur that easily. The main challenge is not so much a sense of incompleteness – continuity as opposed to closure is a vital part of the trio’s aesthetics – but rather a repetition of musical textures and ideas. It seems that nearly every track offers another interpretation of the ‘komorebi’ image: the fleeting wonder of sunlight, newborn leaves, and the interplay of light and shadow, failing to provide more depth to other aspects present on the album, such as the dualities of the visible and the invisible, earth and heaven, life and death.

Komorebi shines brightest when Peltomaa lends her pure voice to her own words, and the sunlight gives way to rain, ice, and forest. The album might have benefited from contrasting shadows alongside the sunlight and tensions of opposites.

A dualism of this sort is imminent on Peltomaa’s collaboration with Belgian double bass player Nathan Wouters in their 2019 album Kaamos, a more experimental and exceedingly minimalistic duo project where sparse dialogues float amidst Nordic darkness. ‘Kaamos’ refers to the sunless period of winter, yet here, its darkness already bears the seeds of summer’s endless daylight. The purity typical of 20th-century modernism meets a sombre free jazz feeling, intertwined with hints of Finnish mythology and woodland melancholy. The result is rough and pure, poetic and enthralling.